Interactions between Categorical Variables in Mixed Graphical Models

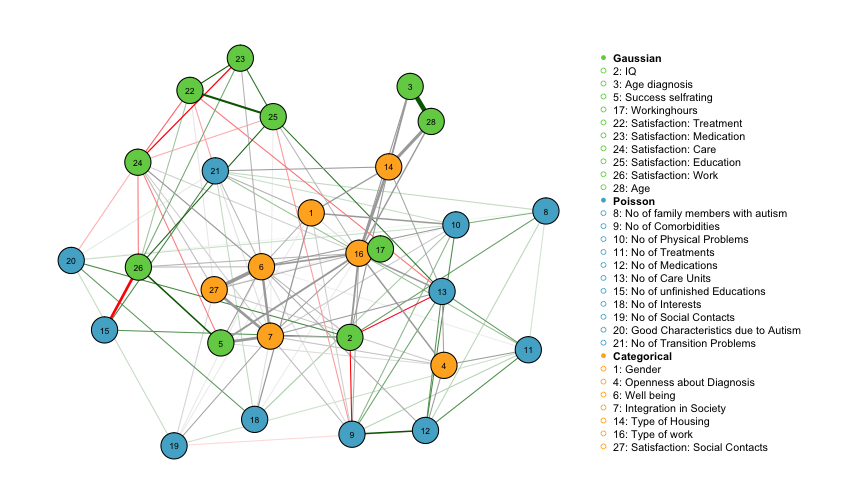

In a previous post we estimated a Mixed Graphical Model (MGM) on a dataset of mixed variables describing different aspects of the life of individuals diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder, using the mgm package. For interactions between continuous variables, the weighted adjacency matrix fully describes the underlying interaction parameter. Correspondinly, the parameters are fully represented in the graph visualization: the width of the edges is proportional to the absolute value of the parameter, and the edge color indicates the sign of the parameter. This means that we can clearly interpret an edge between two continuous variables as a positive or negative linear relationship of some strength.

Interactions between categorical variables, however, can involve several parameter that can describe non-linear relationships. A present edge between two categorical variables, or between a categorical and a continuous variable only tells us that there is some interaction. In order to find out the exact nature of the interaction, we have to look at all estimated parameters. This is what this blog post is about.

We first re-estimate the MGM on the Autism Spectrum Disorder (ADS) dataset from this previous post:

library(mgm)

fit_ADS <- mgm(data = as.matrix(autism_data_large$data),

type = autism_data_large$type,

level = autism_data_large$level,

k = 2,

lambdaSel = 'EBIC',

lambdaGam = 0.25,

pbar = FALSE)## Note that the sign of parameter estimates is stored separately; see ?mgmWe then plot the weighted adjacency matrix as in the previous blog post, however, we now group the variables by their type:

groups_typeV <- list("Gaussian"=which(autism_data_large$type=='g'),

"Poisson"=which(autism_data_large$type=='p'),

"Categorical"=which(autism_data_large$type=='c'))

library(qgraph)

qgraph(fit_ADS$pairwise$wadj,

layout = 'spring', repulsion = 1.3,

edge.color = fit_ADS$pairwise$edgecolor,

nodeNames = autism_data_large$colnames,

color = autism_data_large$groups_color,

groups = groups_typeV,

legend.mode="style2", legend.cex=.45,

vsize = 3.5, esize = 15)

Red edges correspond to negative edge weights and green edge weights correspond to positive edge weights. The width of the edges is proportional to the absolut value of the parameter weight. Grey edges connect categorical variables to continuous variables or to other categorical variables and are computed from more than one parameter and thus no sign is associated with those edges.

While the interaction between continuous variables can be interpreted as a conditional covariances similar to the multivariate Gaussian distributiom, the interpretation of edge-weights involving categorical variables is more intricate as they are a summary of several parameters. In the following two sections we show how to retrieve necessary parameters from the fit_ADS object in order to interpret interactions between continuous and categorical, and betwen categorical and categorical variables.

Interpretation of Interaction: Continuous - Categorical

We first consider the edge weight between the continuous Gaussian variable ‘Working hours’ and the categorical variable ‘Type of Work’, which has the categories (1) No work, (2) Supervised work, (3) Unpaid work and (4) Paid work.

The parameters associated with this interaction can be accessed with the function showInteraction() which takes the mgm() model object and the column numbers of the variables in the interaction as input. In our example, ‘Working hours’ is in column 17, and ‘Type of Work’ is in column 16:

int_16_17 <- showInteraction(object = fit_ADS, int = c(17, 16))

int_16_17## Interaction: 16-17

## Weight: 2.822042

## Sign: NA (Not defined)Printing the object int_16_17 into the console returns the aggregated edge-weight and the fact that no sign is defined for this interaction. The full set of parameters of this interaction can be accessed via int_16_17$parameters:

int_16_17$parameters## $Predict_16

## 17

## 16.1 -14.6460488

## 16.2 -0.7576681

## 16.3 0.7576681

## 16.4 1.4885513

##

## $Predict_17

## 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4

## 17 NA 0.5150313 1.387104 1.792663We see that there is two set of parameters. This is because mgm() uses a nodewise estimation approach. Thus, we have one set of parameters from the regression on variable 16 (“Type of Work”), and one set of parameters from the regression on variable 17 (“Working hours”). We first interpret the regression on “Working hours”. Here, we predict a continuous variable with a categorical variable with four categories. As usual in the regression framework, the first category is omitted as the reference category and the three remaining categories are modeled by indicator functions. The estimates show that if an individual engages in “Supervised Work”, the working hours increase by $\approx 0.52$ compared to if one engages in “No Work”. Similarly, we see that working hours increase by $\approx 1.39$ and $\approx 1.79$ if the individual is engaging in “Unpaid Work” and “Paid Work”, respectively. These results make sense: if one doesn’t work, the working hours are necessarily equal to zero. And if one moves from “Supervised” to “Unpaid” to “Paid” it is also plausible that the working hours increase.

Recall that these parameters are estimated with all other variables in the model. Thus, any interpretation has to be subject to the usual condition that “all other variables remain constant”. The parameter estimates seem somewhat small considering that the response variable is “Working hours”, which should be somewhere between 0 and 40. The reason for the small parameters is that mgm() scales all Gaussian nodes to $\mu=0, \sigma=1$ to ensure that the regularization does not depend on the variance of the node. Note that the reference category is necessary in regression to ensure that the model is identified. When using regularization, however, the model is also identified when modeling \emph{each} category with an indicator function. This is possible in mgm() by setting the argument overparameterize=TRUE.

We now to the interpretation of the second regression on the categorical variable “Type of Work”. Here, we model the probability of every category of the categorical variable (see the glmnet paper for a detailed explanation). In each of the equation for these probabilities, we have a term for the variable “Working hours”. When the associated parameter is negative, increasing “Working hours” decreases the probability of the given category, if the parameter is positive, increasing “Working hours” increases the probability of the given category. We see that the effect of “Working hours” is strongly negative for the probability of “No work”. This makes sense: if “Working hours” is larger than zero, the category “No work” should have probability zero. And correspondingly to the results of the regression on “Working hours”, we see that increasing “Working hours” makes “Paid Work” more likely.

Interpretation of Interaction: Categorical - Categorical

Next we consider the edge weight between the categorical variables 14 ‘Type of Housing’ and the variable 16 ‘Type of Work’ from above. ‘Type of Housing’ has two categories, (a) ‘Not independent’ and (b) ‘Independent’. As in the previous example, we inspect the parameters in this interaction using the function showInteraction():

int_14_16 <- showInteraction(object = fit_ADS, int = c(14, 16))

int_14_16$parameters## $Predict_14

## 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4

## 14.1 NA 0 -0.08987943 -0.6279873

## 14.2 NA 0 0.08987943 0.6279873

##

## $Predict_16

## 14.1 14.2

## 16.1 NA -0.5882431

## 16.2 NA -0.1582227

## 16.3 NA 0.1582227

## 16.4 NA 1.7812274We interpret the regression on variable 14 ‘Type of Housing’. The predicting categorical variable is “Type of Work”, and the first category “No Work” is again treated as a reference category. The first row indicates the parameters in the equation specifying the probability of the first category of “Type of Housing”, namely “Not Independent”. The parameter associated with the category “Supervised Work” is equal to zero, indicating that individuals with no work and supervised work have the same probability of not living independently (keeping all other variables constant). We also see that having “Unpaid Work” decreases the probability of not living independently, and that having “Paid Work” decreases the probability of not living independently much more. We can similarly interpret the second row which shows the parameters in the equation specifying the probability of living independently.

The regression on variable 16 “Type of Work” can be interpreted in the same way and results in the same conclusions as the regression on 14 “Type of Housing”.